Back to the bees!

How do honeybees make their nests? Would you believe that they make all of the wax combs themselves? Where do they get all that wax from? They make it inside their own bodies and it comes out of their abdomens. The organs that make the wax are called wax glands. Here is a picture of a bee making wax.

See that white stuff coming out of her abdomen? A honeybee worker has 8 of these glands, as you can see- four on each side of the abdomen. They squeeze the wax out of their wax glands, then collect it with their mouths and mold like clay, adding it wherever it is needed in the beehive to make their hexagon-shaped cells.

Wild bees hang their combs wherever they can in the hollow tree or other hollow space that they have chosen for a nest. Beekeepers give their bees frames to make their combs in so that the beekeeper can easily move the combs around and gather the honey. Here is a picture of one of those frames with its base, or foundation. The foundation has a hexagon shape printed into it so that the bees will make nice, straight comb for the beekeepers.

Wax gland photo from Denver Beekeeper's Association.

Monday, November 14, 2011

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

How many different kinds of soil are there?

One of you realized from our soil lesson that there were many different kinds of soil. We talked about the three basic particle types of soil. The biggest particles are sand, the medium-sized particles silt, and the smallest particles called clay. Particle types determine the soil's texture. Soil scientists have a classification system using a triangle graph to represent how much of the soil contains each of the three types of particles.

But this is just the beginning of how soil scientists name and classify soil types. There are actually 12 different basic kinds of soil. They are classified by many different features such as texture, kinds of rocks and minerals that the soil comes from, the pH, the environment, and the plants and animals that are present in the soil. Within these 12 basic kinds or soil orders there are many different specific types of soil that are usually named after the place where they were first discovered. These types are called series. In the area of Philipsburg, there is a lot of the soil series called "Andover" for example.

For more information on the 12 soil orders, visit the University of Idaho's Soil Website.

Soil taxonomy poster from soils.usda.gov.

But this is just the beginning of how soil scientists name and classify soil types. There are actually 12 different basic kinds of soil. They are classified by many different features such as texture, kinds of rocks and minerals that the soil comes from, the pH, the environment, and the plants and animals that are present in the soil. Within these 12 basic kinds or soil orders there are many different specific types of soil that are usually named after the place where they were first discovered. These types are called series. In the area of Philipsburg, there is a lot of the soil series called "Andover" for example.

Soil taxonomy poster from soils.usda.gov.

Friday, November 4, 2011

Can people walk on water? (VIDEOS!)

This is a question that came out of the science question box. I decided to keep it lively here by taking a little break from bees. My short answer? No.

What about these guys?

Well, the shoe company that made this ad later admitted that the videos were fake.

Walking on water is actually kind of a common magical trick. Here's a video of the "Masked Magician" showing you how the trick is done in a swimming pool with plastic platforms.

But then how, pray tell, do I explain the little basilisk lizard (aka "The Jesus Lizard" -get it- because it walks on water)? No special effects involved here!

Well, basilisk lizards are a lot smaller than us, and a lot lighter. Water has enough surface tension (strength at its surface) to let small, light things sit or run on the surface. Surface tension comes from the way that water molecules are attracted to each other, so they don't break apart as easily. Also, the basilisk lizard has large feet that spread out when they hit the surface of the water to spread out its weight kind of like wings.

Try this at home to see water's surface tension at work! The surface tension holds a lot more water on the penny than you would think it could!

Bugs are even better at this than basilisk lizards. Behold: The Water Strider!

What about these guys?

Well, the shoe company that made this ad later admitted that the videos were fake.

Walking on water is actually kind of a common magical trick. Here's a video of the "Masked Magician" showing you how the trick is done in a swimming pool with plastic platforms.

But then how, pray tell, do I explain the little basilisk lizard (aka "The Jesus Lizard" -get it- because it walks on water)? No special effects involved here!

Well, basilisk lizards are a lot smaller than us, and a lot lighter. Water has enough surface tension (strength at its surface) to let small, light things sit or run on the surface. Surface tension comes from the way that water molecules are attracted to each other, so they don't break apart as easily. Also, the basilisk lizard has large feet that spread out when they hit the surface of the water to spread out its weight kind of like wings.

Try this at home to see water's surface tension at work! The surface tension holds a lot more water on the penny than you would think it could!

Bugs are even better at this than basilisk lizards. Behold: The Water Strider!

Labels:

basilisk lizard,

surface tension,

video,

water,

water strider

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

Scientific Illustration

I know, it's not a question. This time I am writing just to show you something fun that I learned about today. Today I learned about scientific illustrators. This is a career that involves drawing pictures of things like animals and plants and rocks so that we can understand them better. Remember when we drew a picture of our seed sprouting and labeled the shoot and the root and the cotyledons? Like that, except with everything, not just seeds. Here are some links and some great examples of world-class scientific illustration.

Anglerfish and Amaranthus images by Flickr user Matt Danko. Corn seedling image by Azusa Okuwa.

- California State University Science Illustration program

- Association of Medical Illustrators

- Alison Schroeer entomological illustrations

- Scientific Illustration tumblog

- Guild of Natural Science Illustrators

Anglerfish and Amaranthus images by Flickr user Matt Danko. Corn seedling image by Azusa Okuwa.

Thursday, October 27, 2011

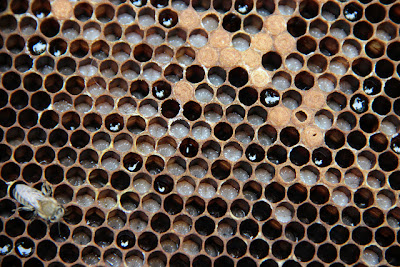

Why are some cells darker than others?

When the comb is brand new, it is white to light yellow. When the bees make new comb we call it "drawing out the comb." Here is a freshly drawn comb.

The comb starts to get darker as it ages. Depending on what is stored in the comb, it will get darker faster. Honey comb doesn't get very dark because honey and nectar are almost clear and cannot color the comb very much. Cells in comb that are used for baby bees (eggs, larvae, and pupae), however, get very dark. That is because that honeybees, like moths, spin a cocoon when they pupate. This cocoon is made of silk strands that come from the mouth of the larva inside. You can't see the cocoon very well because of that wax cap the worker bees put over the cell when the larva when it starts to pupate. Even when you cut open a cell, it is very hard to see the cocoon because it is so thin and sticks to the wall of the cell like wallpaper. The cocoon is darker than the wax, and it makes the wax cells look darker. Once a bee has emerged from a cell, the cell can be re-used for a new larva, so the next larva will spin its cocoon inside the old cocoon of the last larva. The cocoon layers build up like a stack of paper until the cells look very dark indeed. Here is a cross-sectioned (sliced open) cell with an egg. See all the layers at the bottom? Those are old cocoons built up over years.

The pollen also colors the comb. Pollen is usually yellow, but can be brown, red, orange, white, and even purple. These colors all get mixed up when the pollen is stored in the cells to make bee bread. The wax gets stained or colored by all the pollen and starts to look dark.

New comb photo from UNL extension.

The comb starts to get darker as it ages. Depending on what is stored in the comb, it will get darker faster. Honey comb doesn't get very dark because honey and nectar are almost clear and cannot color the comb very much. Cells in comb that are used for baby bees (eggs, larvae, and pupae), however, get very dark. That is because that honeybees, like moths, spin a cocoon when they pupate. This cocoon is made of silk strands that come from the mouth of the larva inside. You can't see the cocoon very well because of that wax cap the worker bees put over the cell when the larva when it starts to pupate. Even when you cut open a cell, it is very hard to see the cocoon because it is so thin and sticks to the wall of the cell like wallpaper. The cocoon is darker than the wax, and it makes the wax cells look darker. Once a bee has emerged from a cell, the cell can be re-used for a new larva, so the next larva will spin its cocoon inside the old cocoon of the last larva. The cocoon layers build up like a stack of paper until the cells look very dark indeed. Here is a cross-sectioned (sliced open) cell with an egg. See all the layers at the bottom? Those are old cocoons built up over years.

The pollen also colors the comb. Pollen is usually yellow, but can be brown, red, orange, white, and even purple. These colors all get mixed up when the pollen is stored in the cells to make bee bread. The wax gets stained or colored by all the pollen and starts to look dark.

New comb photo from UNL extension.

Friday, October 21, 2011

What's in the cells?

The cells are the holes in the honeycomb. They are all-purpose cubbyholes for the bees. Kind of like your desks at school, they use them to organize all their stuff. What kind of stuff do bees have to organize? Lots of stuff!

These are the baby bees. Each baby bee gets its very own cell. They start out as tiny eggs laid by the queen in the bottom of each cell. After they hatch, they are worm-like creatures called larvae. The nurse bees feed them royal jelly, the shiny white liquid around the larvae in this photo. They get bigger and bigger until they pupate, or turn into a pupa inside the cell. The pupa stage is hard to see because as soon as a larva is ready to pupate the worker bees cover up its cell with a cap. Like this:

The cap on the cell is made of wax like the rest of the comb. It protects the pupa from damage. The pupa doesn't eat, so the nurse bees don't need to keep feeding it. Inside the capped cell, the pupa develops into an adult bee.

Here is a newly emerged honeybee. She has just chewed through the cap on her cell and is poking her head out for the first time. She is still very soft and cannot sting or fly for about 24 hours.

Two other things that bees keep in the cells are nectar and pollen. This is their food. The nectar (shiny watery liquid in the above photo) is made into honey. The pollen (yellow powdery stuff in above photo) is made into nutrient-rich food for the bees called "bee bread." Bee bread is just pollen that has been processed by friendly microbes, kind of like the bread that we eat. Our bread uses yeast (a microbe) to rise and taste good.

When the nectar is made into honey, it will have a lot less water in it. The bees cover the honey cells with a wax cap like they do for the pupating honeybee larvae. The cap looks different, though.

So that's what the bees keep in the cells- eggs, larvae, pupae, pollen, bee bread, nectar, and honey! Everything that the beehive needs is stored in the cells.

Bee larvae, emerging bee, pollen and nectar photo by Flickr user Max xx. Capped brood photo by Flickr user KrisFricke. Capped honey photo by Flickr user willsfca.

These are the baby bees. Each baby bee gets its very own cell. They start out as tiny eggs laid by the queen in the bottom of each cell. After they hatch, they are worm-like creatures called larvae. The nurse bees feed them royal jelly, the shiny white liquid around the larvae in this photo. They get bigger and bigger until they pupate, or turn into a pupa inside the cell. The pupa stage is hard to see because as soon as a larva is ready to pupate the worker bees cover up its cell with a cap. Like this:

The cap on the cell is made of wax like the rest of the comb. It protects the pupa from damage. The pupa doesn't eat, so the nurse bees don't need to keep feeding it. Inside the capped cell, the pupa develops into an adult bee.

Here is a newly emerged honeybee. She has just chewed through the cap on her cell and is poking her head out for the first time. She is still very soft and cannot sting or fly for about 24 hours.

Two other things that bees keep in the cells are nectar and pollen. This is their food. The nectar (shiny watery liquid in the above photo) is made into honey. The pollen (yellow powdery stuff in above photo) is made into nutrient-rich food for the bees called "bee bread." Bee bread is just pollen that has been processed by friendly microbes, kind of like the bread that we eat. Our bread uses yeast (a microbe) to rise and taste good.

When the nectar is made into honey, it will have a lot less water in it. The bees cover the honey cells with a wax cap like they do for the pupating honeybee larvae. The cap looks different, though.

So that's what the bees keep in the cells- eggs, larvae, pupae, pollen, bee bread, nectar, and honey! Everything that the beehive needs is stored in the cells.

Bee larvae, emerging bee, pollen and nectar photo by Flickr user Max xx. Capped brood photo by Flickr user KrisFricke. Capped honey photo by Flickr user willsfca.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

What is that white thing?

We saw something extraordinary and amazing when we watched the beehive. We saw the bees carrying away something white and gooey. It looked a little bit like this.

Photo of honeybee removing dead pupa by Kathy Keatley Garvey of the UC Master Gardener Program. Bee larvae photo by Flickr user dreamexplorer.

They ripped it up into small pieces and several bees carried around these bits of white goo all over the hive as if on a mission. The piece of white goo was a bit of a dead bee larva or pupa. Here you can see what they look like when they are alive.

See the small white worms curled up in the bottom of the cells? Those are the larvae. When they get big enough to turn into pupae, the worker bees cover up the cell with a lid made of wax called a cap. That is what those cells are that have a brown cover on them.

You all learned that bees have different jobs in the hive. In addition to foragers that go out to collect nectar and pollen and nurses that feed the larvae, there are "undertaker" bees. Undertaker bees take away the dead and sick bees. Normally, they will take the dead or sick bee away and drop them outside the hive, but our bees couldn't fly out, so our undertaker bees had to keep carrying around the dead bee.

Undertaker bees are very important to the health of the honeybee hive. They are like the doctors of the hive. They observe the bees carefully, and when they sense a bee is sick or dying, they immediately take action to protect the rest of the hive by removing the bee. Scientists who study bees are very interested in finding out how these bees know when another bee is sick and how they decide it is time to remove the sick bee. Some kinds of honeybees, like those from Africa, are really good at removing sick or dead bees. We call these bees "hygienic" because that means they are good at keeping things clean. Other bees, like our European bees, aren't as good at undertaking. If we could find a way to teach our bees to be more hygienic, perhaps we could help solve some of the health problems our honeybees are having right now.

Photo of honeybee removing dead pupa by Kathy Keatley Garvey of the UC Master Gardener Program. Bee larvae photo by Flickr user dreamexplorer.

Labels:

bees,

honeybee health,

hygienic bees,

larvae,

pupae,

undertaker bee

Monday, October 17, 2011

What does it mean to be the queen?

We already learned that the queen bee's main job is to lay all the eggs. But what does that mean? She's the only one laying eggs, so that means that all the worker bees hatched out in the hive are her daughters.

Queen honeybee photo by Flickr user steveburt1947.

Daughters? What about her sons? Well, they're hers too, but they're very different from the worker bees, which are all female. Don't worry, we'll get to the boy bees soon.

Her daughters, the worker bees, follow her around, touching her with their antennae (the pair of "feelers" on their heads). They feed her royal jelly, the same "milk" that the worker bees feed to queen larvae. This group of worker bees that follow the queen bee around are called the "retinue" (RETT-in-you). We call it the retinue because that's the same word that we use for a human queen's followers. The retinue follows the queen because of a perfume that she makes called the queen pheromone (FAIR-oh-moan).

Queen pheromone is powerful stuff. It is a complicated mixture of smells that tells the bees that the queen is present and that she is healthy. Some scientists even think that the queen pheromone is one reason why all the worker bees serve the queen rather than try to be the queen too. It would be like having a perfume that makes you obey anyone wearing it!

Labels:

bees,

pheromones,

queen bee,

queen pheromone,

retinue,

royal jelly

Saturday, October 15, 2011

How do they choose the queen?

Last time we talked about what the queen bee spends most of her life doing: laying eggs. But what about before? How does she get to be the queen? Is there an elaborate ceremony there the other bees all bow and place a crown on her head?

The queen is picked at birth. When the former queen dies, the worker bees select an egg (or a itty bitty larva less than 3 days old) to feed and raise as the next queen. For its entire life, the tiny larva is fed with royal jelly. This royal jelly is a special milk made by the workers. It has lots of nutrients, so the larva grows big. She grows much bigger than a normal worker larva, and the workers build an addition onto her cell to make room. After she gets big enough to metamorphose (go from a larva to an adult bee), she becomes a pupa. The pupa is the stage of her life in which her body converts from a gooey white worm into an adult bee. After a little while, she is ready to emerge as the new queen.

The queen is picked at birth. When the former queen dies, the worker bees select an egg (or a itty bitty larva less than 3 days old) to feed and raise as the next queen. For its entire life, the tiny larva is fed with royal jelly. This royal jelly is a special milk made by the workers. It has lots of nutrients, so the larva grows big. She grows much bigger than a normal worker larva, and the workers build an addition onto her cell to make room. After she gets big enough to metamorphose (go from a larva to an adult bee), she becomes a pupa. The pupa is the stage of her life in which her body converts from a gooey white worm into an adult bee. After a little while, she is ready to emerge as the new queen.

In the normal life of the hive, sometimes the beehive gets too crowded. There are so many bees that they run out of room. It is time for the hive to swarm. Swarming is when the queen flies away with about half of the bees in the hive to find a new nest. The bees that are left behind when the hive swarms have to raise a new queen to take over the egg-laying in their hive. In this case, the old queen has already laid an egg in a special cell called a queen cup. The new queen will develop in the queen cup, fed constantly on royal jelly until she is big enough to be the new queen.

(Queen bee coronation illustration from flickr user art.crazed. Scanned from "The Bee," written and illustrated by Iliane Roels, Grosset & Dunlap, 1969. Queen larvae and queen pupae pictures by Wikimedia user Waugsberg.)

Sorry, no.

The queen is picked at birth. When the former queen dies, the worker bees select an egg (or a itty bitty larva less than 3 days old) to feed and raise as the next queen. For its entire life, the tiny larva is fed with royal jelly. This royal jelly is a special milk made by the workers. It has lots of nutrients, so the larva grows big. She grows much bigger than a normal worker larva, and the workers build an addition onto her cell to make room. After she gets big enough to metamorphose (go from a larva to an adult bee), she becomes a pupa. The pupa is the stage of her life in which her body converts from a gooey white worm into an adult bee. After a little while, she is ready to emerge as the new queen.

The queen is picked at birth. When the former queen dies, the worker bees select an egg (or a itty bitty larva less than 3 days old) to feed and raise as the next queen. For its entire life, the tiny larva is fed with royal jelly. This royal jelly is a special milk made by the workers. It has lots of nutrients, so the larva grows big. She grows much bigger than a normal worker larva, and the workers build an addition onto her cell to make room. After she gets big enough to metamorphose (go from a larva to an adult bee), she becomes a pupa. The pupa is the stage of her life in which her body converts from a gooey white worm into an adult bee. After a little while, she is ready to emerge as the new queen.

In the normal life of the hive, sometimes the beehive gets too crowded. There are so many bees that they run out of room. It is time for the hive to swarm. Swarming is when the queen flies away with about half of the bees in the hive to find a new nest. The bees that are left behind when the hive swarms have to raise a new queen to take over the egg-laying in their hive. In this case, the old queen has already laid an egg in a special cell called a queen cup. The new queen will develop in the queen cup, fed constantly on royal jelly until she is big enough to be the new queen.

(Queen bee coronation illustration from flickr user art.crazed. Scanned from "The Bee," written and illustrated by Iliane Roels, Grosset & Dunlap, 1969. Queen larvae and queen pupae pictures by Wikimedia user Waugsberg.)

Labels:

bees,

eggs,

larvae,

metamorphosis,

pupae,

queen bee,

royal jelly

Monday, October 10, 2011

What does the queen bee do?

The queen bee. She's big. She doesn't look like a normal bee (aka a worker bee). What does it mean to be the queen? What does the queen bee do? The simple answer is, the queen bee lays eggs. Lots of eggs. I think I told you hundreds of eggs per day- I was wrong- it's over a thousand eggs per day! Pretty much non-stop, every 20-30 seconds. Check out this video:

Every time the queen bee sticks her abdomen (tail-like part at the end) into the cell, she lays an egg at the bottom of the cell. These tiny eggs will hatch into tiny larvae, or baby insects. In this picture below the tiny white things that look like rice grains are the eggs, the little white worms that look like they are in a little droplet of liquid are the newborn larvae.

The queen (aka "Big Momma") is normally the only bee that lays eggs in the hive. Her extreme egg-laying at least partially explains why she is so much bigger than the other bees. Like a pregnant mother, she has a big abdomen or belly to grow and hold all of those eggs.

(egg picture from Penn State Cooperative Extension website: http://www.extension.org/pages/26741/inspecting-a-colony)

Saturday, October 8, 2011

Counting Bees

Yesterday I failed to answer the question "How many bees are in there?" about our observation hive. Today I bring you an answer. At least, the best answer I can give you without putting on a bee suit.

For the size frame that we use, they estimated that 1,820 bees was the largest number of bees that you could fit on a frame. There were 3 frames in our observation hives. If all our frames were 100% covered, that would mean that:

1,820 * 3 = 5,460 bees in the observation hive!

That's a lot. To give you an idea how many, the number of people in Philipsburg is about 5,480. So that means you had almost the entire population of Philipsburg (in bees!) on your desk.

5,460 bees in the observation hive!

"That's very specific," you say. You wonder, "How did she get that number?" Well, I am going to answer that question too. I read a scientific paper to figure this out. A scientific paper is an essay that scientists write to tell each other about their experiments.

The paper I read is by Michael Burgett and Intawat Burikam, and was published in 1985.

In this paper, the authors describe an experiment to find out how many bees can live on a standard frame (one of those wooden rectangles with a honey comb in it). They took one frame at a time and two people looked at the frame to estimate what percent of the frame was covered with bees. For example, if only half of the frame had bees on it, they called it 50% covered. If all of the frame was covered by a layer of bees, the frame was 100% covered. Then they took the frames and killed all of the bees with gas (sad!). They killed the bees so that they could weigh them more easily. Don't worry- there were a lot more bees still in the hives. They used our method of weighing the bees to figure out how many there were. So they could use their percent covering estimates and pair them with a number of bees to estimate how many bees on average could fit on the frame (with the help of some secondary school math).For the size frame that we use, they estimated that 1,820 bees was the largest number of bees that you could fit on a frame. There were 3 frames in our observation hives. If all our frames were 100% covered, that would mean that:

1,820 * 3 = 5,460 bees in the observation hive!

5,460 bees in the observation hive!

That's a lot. To give you an idea how many, the number of people in Philipsburg is about 5,480. So that means you had almost the entire population of Philipsburg (in bees!) on your desk.

Labels:

bees,

counting,

estimating,

finding out,

papers,

weighing

Friday, October 7, 2011

How many bees are in there?

Several of you asked about how many bees there were in the observation hive. Boy, my first question and I'm going to failboat it. I have no idea. A lot. A whole lot of bees.

If we wanted to know the answer to that, how could we find out? (Remember when we talked about "finding things out" as a definition of science?) Think about it...

Ok, here are some ideas I came up with:

1) Count them one by one. This would be really hard because the bees move around so much. Maybe instead of counting them while they are moving, you could take a photo and count them in the photo. This would take a long time. Maybe I could write a computer program to count bees in the photo for me. But then what about the bees that are hiding in the cells (the holes in the honey comb)? I don't think this is the best method.

2) Weigh them. First, weigh groups of bees, maybe 10 to 20 bees at a time in a cup. Subtract the weight of the cup and then divide by how many bees you weighed to figure out about how much a single bee weighs. Then take all the bees out of the hive, shake them into a bucket or something and weigh all the bees, subtracting the weight of the bucket. Divide this weight of all the bees by the weight of a single bee to figure out how many bees there are.

Let's do the math!

Say I grab 10 bees in a net and put them in a jar and the jar full of bees weighs 50.3g (grams). I let the bees go, then weigh the empty jar (with its lid) and it weighs 49.3g.

50.3g - 49.3g = 1 g

Means that the 10 bees (without the jar) weigh 1 g. That means that each bee weighs 0.1 g (1g / 10 bees = 0.1g) or one tenth of a gram.

Next step- get all the bees out of the beehive and into a bucket. I'd need a bee-suit to keep me from getting stung. and a smoker to make smoke. Smoke makes the bees think that there's a fire, so they start drinking nectar and honey and mostly ignore beekeepers. I'd take my hive tool too. It's a little pry-bar for separating the boxes and frames of the hive. Bees like to seal everything up with "bee glue," so beekeepers need to have a hive tool to pry things apart in the hive.

Next step- get all the bees out of the beehive and into a bucket. I'd need a bee-suit to keep me from getting stung. and a smoker to make smoke. Smoke makes the bees think that there's a fire, so they start drinking nectar and honey and mostly ignore beekeepers. I'd take my hive tool too. It's a little pry-bar for separating the boxes and frames of the hive. Bees like to seal everything up with "bee glue," so beekeepers need to have a hive tool to pry things apart in the hive.

I'd open up the cover and pull the frames out one at a time, shaking the bees off into a bucket with a lid. Bees would be flying around everywhere every time I shook a new frame or opened the bucket. It would be really hard to get all of the bees off of the frame because they cling to the frames really well. Once I shook all the bees I could into the bucket, I'd have to go weigh the bucket. Let's say the bucket full of bees weighed 1,627 g. After I dump all the bees back into the hive, I weigh the bucket (maybe I should have done this before I put the bees in, eh?), and it weighs around 907 g.

Then I subtract the weight of the bucket from the weight of the bees+bucket to get 720 g for the weight of all the bees in the observation hive. Since we measured the weight of one bee to be 0.1 g, we divide 720 g by 0.1 g to get 7,200 bees! I told you it was a lot of bees!

Then I subtract the weight of the bucket from the weight of the bees+bucket to get 720 g for the weight of all the bees in the observation hive. Since we measured the weight of one bee to be 0.1 g, we divide 720 g by 0.1 g to get 7,200 bees! I told you it was a lot of bees!What's that you say? I didn't actually do the experiment? I can't say that I have 7,200 bees when I never weighed a single bee? Ok, well then I'll get the bee-suit out and you can help me.

Oh- you don't want to do all that work to get that number? You don't want to even have to go outside? Boy, you guys are lazy! Then again, maybe you have a point. When I shake all the bees out of the hive, I will probably end up hurting a lot of them. A bunch of them will fly away and never make it in the bucket anyhow. And I would never want to lose the queen bee! Next time, I'll reveal a simpler and easier way to estimate the number of bees in my observation hive.

An Introduction

I have started this blog to catalog answers to science questions posed by 5th grade students. I am currently a NSF GK-12 fellow, serving at North Lincoln Hill Elementary School. The 5th-grade students that I teach are always asking me fascinating questions- better questions, sometimes, than adults ask.

My first assignment is to answer a large number of questions that the students wrote about honeybees. I brought an observation beehive into the classroom on my first teaching day and the students were really buzzing with questions. I had them write them all down and collected them, promising a response. The students have since learned quite a bit about bees, reading two different articles and making content diagrams. But since I promised, and since I need the practice, and since I don't think all of their questions were covered, I'm going to try to answer all of them anyway! Get ready!

My first assignment is to answer a large number of questions that the students wrote about honeybees. I brought an observation beehive into the classroom on my first teaching day and the students were really buzzing with questions. I had them write them all down and collected them, promising a response. The students have since learned quite a bit about bees, reading two different articles and making content diagrams. But since I promised, and since I need the practice, and since I don't think all of their questions were covered, I'm going to try to answer all of them anyway! Get ready!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)